Der Hut in Peru ist weit mehr als nur ein Schutz vor Sonne oder Kälte. Er ist ein Symbol der Geschichte, der Identität und der Zugehörigkeit – eine Sprache ohne Worte, die von den Wurzeln jedes Volkes erzählt. Von den zeremoniellen Kopfbedeckungen des alten Peru bis zu den farbenfrohen regionalen Hüten, die noch heute Feste und den Alltag begleiten, spiegelt jedes Stück ein lebendiges Erbe wider, das sich zwischen Kunst, Weltanschauung und kollektiver Erinnerung webt.

Im Buch „Sombreros y tocados en el Perú – Eine Begegnung mit Identität und kultureller Vielfalt“ laden uns die Autorinnen Amparo Baca Polanco und Mirta Peralta Flores zu einer visuellen und anthropologischen Reise durch das Land ein. Sie zeigen, wie der Hut zu einer kulturellen Sprache wird, die Herkunft, Beruf, Geschlecht oder Familienstand ihres Trägers offenbart.

Das Werk ist in drei große Abschnitte gegliedert:

- Kopfschmuck von gestern und heute, der die symbolische Bedeutung der prähispanischen Schmuckformen – aus Federn, Metallen oder feinen Textilien – und ihre Wandlung im Laufe der Zeit beleuchtet.

- Die Hüte in Peru, wo sich europäische Einflüsse der Kolonialzeit mit andinen und amazonischen Traditionen verbinden und einzigartige Formen entstehen.

- Regionale Hüte, eine Hommage an die Vielfalt des Landes: der Toquilla-Strohhut aus Cajamarca, die Cusqueña-Montera, die Wollmütze aus Puno, der elegante Arequipa-Hut oder die weiten Kopfbedeckungen des Altiplanos – jeder erzählt seine eigene Geschichte.

Hinter jedem Design stehen Hände, die mit Geduld und Stolz arbeiten. Die Handwerker formen, flechten und besticken Hüte, die nicht nur vor dem Klima schützen, sondern Erinnerung und Identität der Völker bewahren. In ihnen spiegelt sich der Geist einer Nation wider, die noch immer mit ihrer Vergangenheit durch Fäden, Farben und Formen spricht.

Wie die Autorinnen betonen, ist der Hut eine sichtbare Spur der Kultur, ein lebendiges Erbe, das uns einlädt, Peru mit Respekt, Bewunderung und Dankbarkeit für die Weisheit seiner Gemeinschaften zu betrachten.

Baca Polanco, Amparo & Peralta Flores, Mirta (Hrsg.) Sombreros y tocados en el Perú: un encuentro con la identidad y diversidad cultural. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú, 2018

Sombreros y tocados en el Perú: identidad y diversidad cultural

En el Perú, el sombrero es mucho más que protección contra el sol o el frío. Es símbolo de historia, identidad y pertenencia: un lenguaje silencioso que habla de las raíces de cada pueblo. Desde los tocados ceremoniales del antiguo Perú hasta los coloridos sombreros regionales que aún acompañan las fiestas y la vida cotidiana, cada pieza refleja un patrimonio vivo tejido entre el arte, la cosmovisión y la memoria colectiva.

En el libro “Sombreros y tocados en el Perú: un encuentro con la identidad y diversidad cultural”, las autoras Amparo Baca Polanco y Mirta Peralta Flores nos invitan a un recorrido visual y antropológico por el país, mostrando cómo el sombrero se convierte en un lenguaje cultural capaz de revelar el origen, el oficio, el género o la condición social de quien lo porta.

La obra se organiza en tres grandes apartados:

- Los tocados de ayer y hoy, que exploran el simbolismo ancestral de los adornos prehispánicos —de plumas, metales o finos tejidos— y su transformación a lo largo del tiempo.

- Los sombreros en el Perú, donde la influencia europea colonial se entrelaza con las tradiciones andinas y amazónicas, dando origen a formas y estilos únicos.

- Sombreros regionales, un homenaje a la diversidad del país: el sombrero de paja toquilla de Cajamarca, la montera cusqueña, el chullo puneño, el elegante sombrero arequipeño o los amplios tocados del Altiplano —cada uno con su historia y su significado.

Detrás de cada diseño hay manos que trabajan con paciencia y orgullo. Las y los artesanos tejen, moldean o bordan sombreros que no sólo protegen del clima, sino que resguardan la memoria y la identidad de los pueblos. En ellos late el espíritu de una nación que sigue dialogando con su pasado a través de los hilos, los colores y las formas.

Como recuerdan las autoras, el sombrero es una huella visible de la cultura, un patrimonio vivo que nos invita a mirar al Perú con respeto, admiración y gratitud por la sabiduría de sus comunidades.

Baca Polanco, Amparo & Peralta Flores, Mirta (eds.). Sombreros y tocados en el Perú: un encuentro con la identidad y diversidad cultural. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú, 2018.

Hats and Headdresses in Peru: Identity and Cultural Diversity

In Peru, the hat is much more than protection from the sun or the cold. It is a symbol of history, identity, and belonging, a silent language that tells the story of every people’s roots. From the ceremonial headdresses of ancient Peru to the colorful regional hats that still accompany daily life and celebrations, each piece reflects a living heritage woven between art, worldview, and collective memory.

In the book “Sombreros y Tocados en el Perú: An Encounter with Identity and Cultural Diversity,” authors Amparo Baca Polanco and Mirta Peralta Flores take us on a visual and anthropological journey through the country. They reveal how the hat becomes a cultural language, capable of expressing origin, profession, gender, or marital status.

The work is organized into three main parts:

- Headdresses of Yesterday and Today, exploring the ancestral symbolism of pre-Hispanic adornments made of feathers, metals, or fine textiles, and their transformation through time.

- Hats in Peru, showing how European colonial influences intertwined with Andean and Amazonian traditions, giving rise to unique shapes and styles.

- Regional Hats, a tribute to the country’s diversity: the straw hat from Cajamarca, the montera from Cusco, the woolen chullo from Puno, the elegant Arequipa hat, or the wide headdresses of the high plateau — each with its own story and meaning.

Behind every design are hands that work with patience and pride. The artisans weave, shape, or embroider hats that not only protect from the weather but also preserve the memory and identity of their people. Within them lives the spirit of a nation still in dialogue with its past — through threads, colors, and forms.

As the authors remind us, the hat is a visible mark of culture, a living heritage that invites us to look at Peru with respect, admiration, and gratitude for the wisdom of its communities.

Baca Polanco, Amparo & Peralta Flores, Mirta (eds.) Sombreros y tocados en el Perú: un encuentro con la identidad y diversidad cultural. Ministry of Culture of Peru, 2018.

Ch’uku kikin Perúpi: Runaq sutinchaynin, yachaynin, sumaq kayninwan

Perú llaqtapi ch’ukuqa mana sapa p’unchaykama k’uriyta hap’iqchu, ni q’ayanmanta waqaychakuqchu. Ch’ukuqa ñawpaq kausaypa, runa sutinchaypa, llapa ayllukunapa wiñay kawsaypa rimayniyoq. Ñawpaq ch’ukuqkunamanta –plumas, qori, lliw lliw awaspi ruwasqa– kunan p’unchaykunaqa llimp’i, salliwan, tinkuywanmi qillqasqa kawsayta rikuchin.

Libropi “Sombreros y tocados en el Perú: un encuentro con la identidad y diversidad cultural”, qillqakuna Amparo Baca Polanco wan Mirta Peralta Flores rimanakuwayku llaqtakunapaq, ima ruwasqawan, ima saminwan ch’uku runakunapa kausaymanmi riman. Ch’ukuqa runaq rimay, kay pachapi ñawpaq pacha rimayta ruwachiqmi.

Libroq rakinakunam kinsa kaqmi:

- Ñawpaq ch’ukuqkunamanta kunan p’unchaykama, rimaykunata taripayku –ñawpaq runakunaq sumaq willakuykunata plumas, q’ori, awaspi ruwasqakunamanta–.

- Perú ch’ukuqkunamanta, llaqtapi ch’askachaykunamanta, hispanumanta hamuq ima yachaywan tinkusqa, llaqtapa yachayninwanmi ch’ukukunam ruwasqa.

- Suyukunaq ch’ukuqkuna, ñawpaqpiqa llaqtapaq willakuy: Cajamarcamanta paja ch’uku, Cuscomanta montera, Punomanta chullu, Arequipamanta sumaq ch’uku, sierra hatunmanta wiñay ch’uku –sapa huk willakuywanmi hamun.

Sapa ch’ukuq qhipan runakuna ruwanku sonqowan, llank’ayninwan, sumaq llapallan. Ch’ukuqa mana chakiwanmi ruwasqa, ancha sonqoykuwan, runaq yuyaynin, wiñay kawsayninmi qhawachin. Ch’ukuqa kay pachapi ñawpaq pachawan rimakuq runa llaqtaykuta rikuchin –salliy, llimp’i, sutiwan.

Qillqakuna nirqanku, ch’ukuqa runaq kawsayta qhawachiq unay rikch’ayniyoqmi, Perúta qhawachiyta munachkanmi yupaychasqa, kawsayniykuta yachayniykuta riqsichiq llaqtakunapaq.

Baca Polanco, Amparo & Peralta Flores, Mirta (2018). Sombreros y tocados en el Perú: un encuentro con la identidad y diversidad cultural. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú.

Die Inka-Ikonographie in den Textilien

Einleitung

Die Textilien des alten Peru waren nicht nur einfache Kleidungsstücke oder Schmuck. Sie waren visuelle Codes, durchdrungen von Symbolen, die Macht, Spiritualität und Identität vermittelten. In der Welt der Inka war jeder Faden Teil einer stillen Sprache, die von der Beziehung zwischen Menschen, Natur und Göttern erzählte.

1. Die Tocapus: eine geometrische Sprache

Eines der charakteristischsten Symbole der Inka-Ikonographie sind die Tocapus: Quadrate oder Rechtecke mit geometrischen Mustern im Inneren. Sie erschienen auf zeremoniellen Tuniken (uncu) und wurden hauptsächlich von Adeligen und Herrschern getragen.

Jeder tocapu hatte eine besondere Bedeutung, die von eroberten Territorien bis zu kosmischen oder sozialen Konzepten reichen konnte. Manche Forscher vermuten sogar, dass dieses System eine Art proto-schriftliches Zeichensystem gewesen sein könnte, ein visuelles Wissen, das nur der Elite zugänglich war.

2. Farben, die sprechen

In der Inka-Textilkunst waren Farben keine bloße Dekoration, sondern Botschaften an sich. Rot stand für Blut und Lebenskraft, Gelb war mit der Sonne und dem Gold verbunden, und Schwarz symbolisierte Dualität und Geheimnis. Diese Farben, gewonnen aus natürlichen Farbstoffen, hatten auch rituellen Wert: Beim Färben der Fasern wurde die Energie der Erde und der Pflanzen übertragen.

3. Symbole von Macht und Spiritualität

Kleidung mit ikonographischen Motiven war mehr als ein Kleidungsstück: sie war ein Instrument der politischen Legitimation und religiösen Zeremonie.

abgebildet wurden heilige Tiere wie der Puma, Symbol der Stärke; der Kondor, Bote zwischen Himmel und Erde; und die Schlange, verbunden mit Weisheit und der Unterwelt (Uku Pacha).

4. Textilien als Spiegel des Reiches

Die staatlichen Werkstätten (acllas und cumbi camayoc) stellten feinste Stoffe wie den Cumbi her, gewebt aus Vikunja- oder Baby-Alpaka-Fasern, ausschließlich für den Adel und die wichtigsten Zeremonien. Die Qualität war so außergewöhnlich, dass viele dieser Stoffe bis heute ihren Glanz und ihre Farben bewahrt haben.

Ein Textil mit Inka-Ikonographie zu besitzen oder zu tragen bedeutete nicht nur Reichtum: Es war, als trüge man eine Erklärung von Macht, Abstammung und kosmischer Verbindung am eigenen Körper.

5. Lebendige Kontinuität

Obwohl das Inka-Reich vor über fünf Jahrhunderten unterging, lebt die Textiltradition in den Andengemeinschaften von Cusco, Ayacucho und Puno weiter. Geometrische Motive, Farbkombinationen und die Art des Spinnens und Webens bewahren bis heute die Essenz der alten Ikonographie. Jedes Kleidungsstück ist zugleich ein Erbe und eine Form kulturellen Widerstands.

Schlussfolgerung

Die Inka-Ikonographie in den Textilien erinnert uns daran, dass Weben nicht nur ein Handwerk ist, sondern eine heilige Schrift. In jedem Muster liegt eine Botschaft von Identität, Spiritualität und Macht, die noch heute aus den Fäden der Zeit zu uns spricht.

📚 Bibliographie

- d’Harcourt, R. (1934). Textiles of Ancient Peru and Their Techniques. Paris: Paul Geuthner. (Kapitel V: Textile Ikonographie, S. 123–156).

- Rowe, J. H. (1961). Inca Culture at the Time of the Spanish Conquest. In J. H. Steward (Hrsg.), Handbook of South American Indians (Bd. 2, S. 183–330). Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Cummins, T. (2002). Toast to the Inca: Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Quero Vessels. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Murra, J. V. (1975). Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. (Kapitel III: Textilorganisation und Tribut).

La iconografía inka en los textiles

Introducción

Los textiles del antiguo Perú no fueron simples objetos de abrigo o adorno. Fueron auténticos códigos visuales, cargados de símbolos que transmitían poder, espiritualidad e identidad. En el mundo inka, cada hilo estaba pensado como parte de un lenguaje silencioso que hablaba de la relación entre el ser humano, la naturaleza y los dioses.

1. Los Tocapus: un lenguaje geométrico

Uno de los símbolos más característicos de la iconografía inka son los tocapus: cuadrados o rectángulos con diseños geométricos en su interior. Aparecían en túnicas ceremoniales (uncu) y eran usados principalmente por la nobleza y los gobernantes.

Cada tocapu tenía un significado particular, que podía representar desde territorios conquistados hasta conceptos de orden cósmico o social. Algunos investigadores sostienen que este conjunto de símbolos podría haber sido un sistema protoescrito, un lenguaje visual que solo la élite conocía.

2. Colores que comunican

En la textilería inka, los colores no eran decorativos, sino mensajes en sí mismos. El rojo evocaba la sangre y la energía vital; el amarillo estaba asociado al sol y al oro; el negro representaba la dualidad y el misterio. Estos colores, obtenidos de tintes naturales, tenían además un valor ritual: al teñir las fibras, se estaba transmitiendo la energía de la tierra y de las plantas.

3. Símbolos de poder y espiritualidad

Las prendas con motivos iconográficos eran más que vestimenta: eran instrumentos de legitimación política y ceremonial religiosa. Vestir un textil con ciertos símbolos convertía al gobernante en mediador entre los dioses y los hombres.

Se representaban animales sagrados como el puma, símbolo de fuerza; el cóndor, mensajero entre el cielo y la tierra; y la serpiente, vinculada a la sabiduría y al mundo subterráneo (Uku Pacha).

4. Textiles como reflejo del imperio

Los talleres estatales (acllas y cumbi camayoc) producían textiles finísimos como el cumbi, tejido con fibra de vicuña o alpaca bebé, reservado para la nobleza y las ceremonias más solemnes. La calidad era tan extraordinaria que, incluso hoy, muchos de estos tejidos conservan su brillo y color tras siglos de historia.

Poseer o portar un textil con iconografía inka no solo significaba riqueza: era llevar sobre el cuerpo una declaración de poder, linaje y conexión cósmica.

5. Continuidad viva

Aunque el imperio inka desapareció hace más de cinco siglos, la tradición textil sigue viva en comunidades andinas del Cusco, Ayacucho y Puno. Los motivos geométricos, las combinaciones de colores y la manera de hilar y tejer aún conservan la esencia de la iconografía ancestral. Cada prenda es, al mismo tiempo, un legado y una forma de resistencia cultural.

Conclusión

La iconografía inka en los textiles nos recuerda que el tejido no es solo un arte manual, sino una escritura sagrada. En cada diseño se guarda un mensaje de identidad, espiritualidad y poder, que sigue hablándonos desde el hilo mismo del tiempo.

📚 Bibliografía

- d’Harcourt, R. (1934). Textiles of Ancient Peru and Their Techniques. Paris: Paul Geuthner. (Cap. V: Iconografía textil, pp. 123–156).

- Rowe, J. H. (1961). Inca Culture at the Time of the Spanish Conquest. In J. H. Steward (Ed.), Handbook of South American Indians (Vol. 2, pp. 183–330). Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Cummins, T. (2002). Toast to the Inca: Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Quero Vessels. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Murra, J. V. (1975). Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. (Cap. III: Organización textil y tributo).

Inka Iconography in Textiles

Introduction

The textiles of ancient Peru were not merely garments or ornaments. They were visual codes, imbued with symbols that conveyed power, spirituality, and identity. In the Inka world, every thread was part of a silent language that spoke of the relationship between human beings, nature, and the gods.

1. Tocapus: a geometric language

One of the most characteristic symbols of Inka iconography are the tocapus: squares or rectangles with geometric patterns inside. They appeared on ceremonial tunics (uncu) and were mainly worn by nobles and rulers.

Each tocapu carried a particular meaning, which could represent conquered territories, cosmic concepts, or social order. Some scholars even suggest that this system may have been a form of proto-writing, a visual language accessible only to the elite.

2. Colors that speak

In Inka textiles, colors were not decorative elements, but messages in themselves. Red evoked blood and vital energy; yellow was associated with the sun and gold; and black symbolized duality and mystery. These colors, obtained from natural dyes, also had ritual value: by dyeing the fibers, the energy of the earth and plants was transmitted.

3. Symbols of power and spirituality

Garments with iconographic motifs were more than clothing: they were instruments of political legitimacy and religious ceremony.

Sacred animals were often represented: the puma, symbol of strength; the condor, messenger between heaven and earth; and the serpent, linked to wisdom and the underworld (Uku Pacha).

4. Textiles as a mirror of the empire

State workshops (acllas and cumbi camayoc) produced the finest textiles, such as cumbi, woven from vicuña or baby alpaca fiber, reserved exclusively for the nobility and the most solemn ceremonies. The quality was so extraordinary that many of these textiles still retain their shine and color after centuries.

To own or wear a textile with Inka iconography was not only a sign of wealth: it meant carrying a statement of power, lineage, and cosmic connection on one’s body.

5. Living continuity

Although the Inka Empire disappeared more than five centuries ago, the textile tradition is still alive in Andean communities in Cusco, Ayacucho, and Puno. Geometric motifs, color combinations, and methods of spinning and weaving preserve the essence of the ancient iconography. Each garment is both a legacy and a form of cultural resistance.

Conclusion

The iconography of the Inka in textiles reminds us that weaving was not only a craft, but a sacred writing. In every design, a message of identity, spirituality, and power is preserved, still speaking to us from the very threads of time.

📚 Bibliography

- d’Harcourt, R. (1934). Textiles of Ancient Peru and Their Techniques. Paris: Paul Geuthner. (Chapter V: Textile Iconography, pp. 123–156).

- Rowe, J. H. (1961). Inca Culture at the Time of the Spanish Conquest. In J. H. Steward (Ed.), Handbook of South American Indians (Vol. 2, pp. 183–330). Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Cummins, T. (2002). Toast to the Inca: Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Quero Vessels. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Murra, J. V. (1975). Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. (Ch. III: Textile organization and tribute).

Inkaq siq’ina awanakunapi

(La iconografía inka en los textiles)

Qallariy (Introducción)

Ñawpaq Perup awanakuna manaraq p’achakunaqa kanan hinaqa manaraq q’aspikunaqa kanchu. Kaykunaqa siq’inakuna kachkanku, runakunapa kallpanta, espíritu nisqata, identidadta willakuq. Inka llaqtapi, sapa millmaqa rimaymi karqa, runa, pachamama, apukunawan kuska rimaykuq.

1. Tocapu: siq’i geometrico

Inkaq siq’inakunapi, achka rikhusqa kanku tocapu nisqa: cuadrado icha rectangular siq’iwan tiqrasqa. Kaykunataqa uncu (p’acha ceremonial) nisqapi churakunku, achkaqa kurakuna, sinchi inkap runakunapa.

Sapa tocapuqa mana chikninchu, hukninmanta qhichwaqa: suyukunata, hananpachapi orden nisqata, runa llaqtakunapa kuskachayta rikhuchin. Achka yachaqkunaqa ñawpaq qillqa hina, proto-qillqa ñinmi karqan, yachaykunataqa kurakuna sapa-sapalla rikhuykuq.

2. Llimp’i rimaykuq

Inkaq awanakunapiqa, llimp’ikunam q’aspikuna q’aspichiqchu, ancha rimaykuna karqan. Pukaqa yawarnin kawsaymi; q’illuqa intiq, qoriwan tinkusqa; yanaqa yanantin, kaykunawanqa ch’inkayta rikuchin. Kay llimp’ikunataq allpa yuraqkunam qukun, manaraqqa llumpay ritualmi karqan: millmata llimp’ichispa, pachamaman kallpanta, yuraqkunapa saminta churanku.

3. Simbolokuna: kallpa, espíritu

Siq’iwan rurasqa p’achakunaqa manam sapa llusqalla kanchu: politico legitimación hina, ritual religioso hinaqa.

Kaykunapiqa apukunapa uywakunam rikch’akunku: puma, kallpa nisqa; kuntur, hananpacha, kaypacha, ukhu pacha chaskiq; amaruqa, yachaywan, uku pachawan tinkuq.

4. Awanakuna: imperionpa rikch’aynin

Estadoq awana wasikunapi (aclla icha cumbi camayoc) rurasqakunaqa sumaq cumbi nisqa millmata, vicuña icha millma alpaca wawawan rurasqakunata, kurakuna, sinchi ceremoniawanllapi churaq. Kay awanakunaqa aswan sumaq karqa, chayrayku kunan punchawqa llumpay q’illqiywan kawsasqa kachkan.

Inka siq’ina p’acha hap’isqa icha churayqa mana qhapaqlla kanchu: poder, ayllu runanpa ayllu rimaynin, hanan kallpanwan tinkusqa hinam karqa.

5. Kawsaykunapi qhispiykuna

Inkaq imperionqa ñawpaq 500 wataqa chinkasqanmanta, awanakunaqa kawsaymanmi ñawpaqkama kachkan Cusco, Ayacucho, Puno llaqtakunapi. Geometrico siq’inakuna, llimp’i tinkunakuna, millma awanay rurayninqa kunan punchawpas ñawpaq rimayninta apamun. Sapa p’achaqa chaymantataq huk qhispiy, qhapaq kayninkuta rikuchin.

Tukuy ñiqi (Conclusión)

Inkaq siq’ina awanakunapiqa ñuqanchikta yachachin: awanayqa manaraq ruk’ana sapa llusqalla kanchu, qillqa sagrada kachkan. Sapa siq’inapiqa kawsayta, espíritu nisqata, poder nisqata churasqa kachkan, kunan punchawpas millmakunam ñawpaq watakunamanta rimachkan.

📚 Bibliografía

- d’Harcourt, R. (1934). Textiles of Ancient Peru and Their Techniques. Paris: Paul Geuthner. (Capítulo V: Iconografía textil, pp. 123–156).

- Rowe, J. H. (1961). Inca Culture at the Time of the Spanish Conquest. In J. H. Steward (Ed.), Handbook of South American Indians (Vol. 2, pp. 183–330). Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Cummins, T. (2002). Toast to the Inca: Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Quero Vessels. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Murra, J. V. (1975). Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. (Cap. III: Organización textil y tributo).

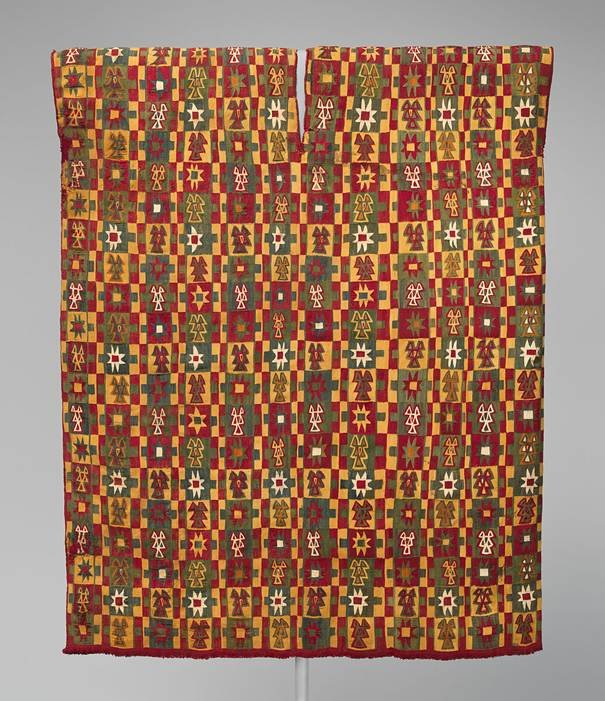

Miniature Dress / Votive checkerboard tunic

Amplios ejemplos de tocapus y tejidos ceremoniales incas.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Detalle textil con iconografía Inca (cumbi tipo panel)

Alta calidad visual y simbolismo fuerte.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art+1

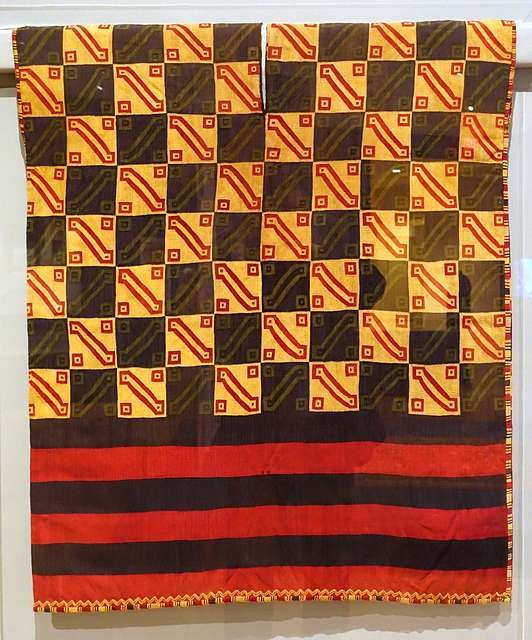

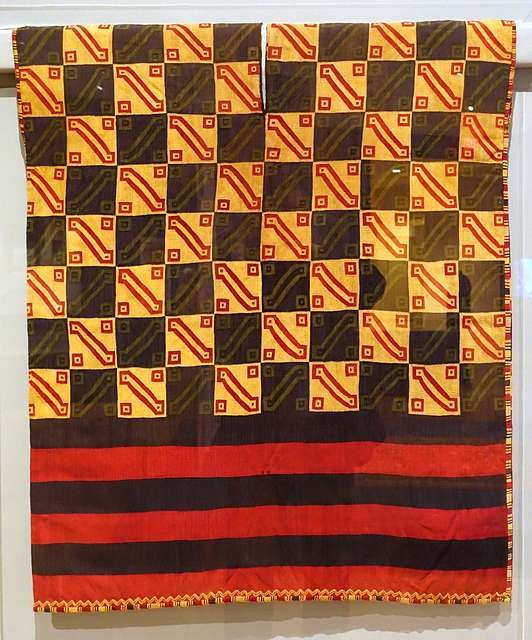

Patrón de cuadrícula tradicional (tocapu style)

Ideal para explicar la geometría simbólica de los textiles.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

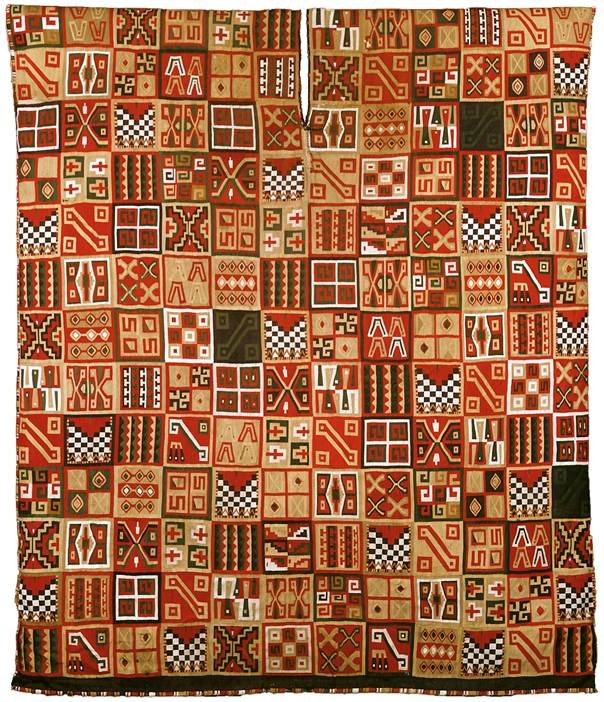

Textil colonial en malla tipo collage (continuidad ancestral)

Muestra evolución y adaptación pos-inka, muy evocativo.

Comments

There are no comments yet.